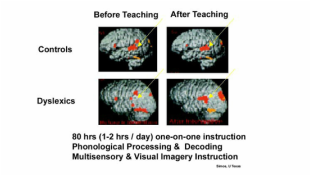

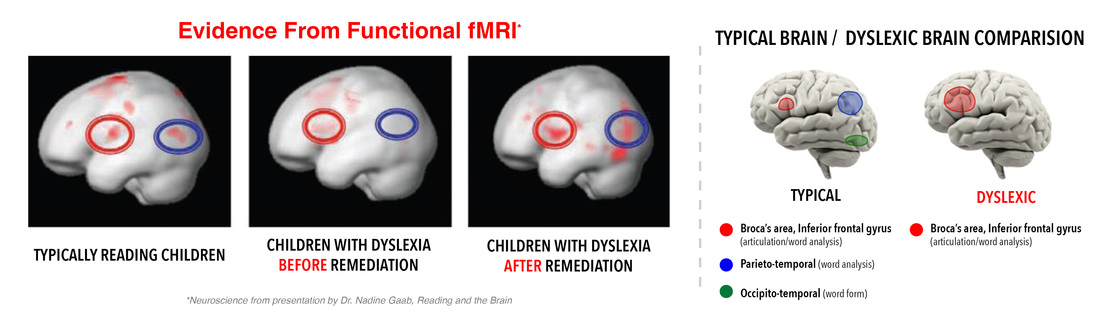

Nancy Duggan, Executive Director, DDMA Some children do not read proficiently by third grade even when parents and teachers seem to be doing all they can. What does neuroscience tell us about this problem? Researchers have been studying the process of how we learn to read for over 30 years using Neuroscience. That is not a long time in the world of science. We have been studying the planets scientifically since Copernicus in the 1500s. With that kind of time invested, no wonder we could send rockets to the moon before our kids were born; but teaching them to read remains a challenge. What we now call dyslexia was first mentioned in the 1870s. But just as Copernicus and his telescope started scientific study in the 1500s, proving that the earth went around the sun, which over time lead us to walk on the moon, using neuroscience and brain imaging technology to study dyslexia has advanced what we know about how brains learn to read. These advancements, if transferred to the classroom, could improve reading for dyslexic students. Neuroscience1 recently has been making great strides in dyslexia research and MRI technology has played a part. In particular, fMRI technology which uses a Magnetic Resonance Imaging process to make observations of how brains are functioning (the f in fMRI). Scientists are able to evaluate the areas of brain activity and the amount of energy that our brain’s specialized areas are using. There is not one area of the brain that is dedicated to reading. Neuroscientists explain that there are many areas of specific brain activity that naturally process vision, language and/or memory. These areas must be taught to work together, these multiple areas communicating through brain pathways are built by learning.2 By using many fMRI images together neuroscientists observe changes and developments that indicate how these regions are working, and working together, in good and poor readers. Our brains are constantly adapting and changing as we learn and the ability to make these observations has provided evidence of the differences that can naturally occur between individuals trying to adapt and learn the process of reading. Neurodiversity or cerebrodiversity are new terms to reflect the differences in healthy functioning brains that process differently from each other. Understanding the differences in brain processing, in what Dr. Nadine Gaab describes as the typical and atypical (ADHD and/or Dyslexia) reading brain, is a valuable consideration when choosing instruction, intervention and assessments for reading instruction of all students. Dr. Gaab and colleagues have found that these differences are present at birth and Dr. Gabrieli and Dr. Norton provide evidence that as early as kindergarten, it is valid, effective, and advisable to screen for these differences and actively ensure that instruction is specific to the needs of these children. They are not alone in their research and there is ample evidence for the neurobiological existence of dyslexia. Unfortunately, like many folks in the time of Copernicus who did not at first believe or understand that the planets went around the sun because they had been taught that the sun circled the earth, many educators have been told that dyslexia is not real or doesn’t matter. Likewise, even when the word dyslexia is used, parents and teachers who are using the word without the current neurobiological meaning and the implications of the latest research may not find the specific instruction that will be effective. For example, the SLD (Specific Learning Disability) Module of instruction for the Massachusetts Department of Education incorrectly describes dyslexia as a common term that is used for “the reading related manifestations of learning disabilities”.3 This highlights the commonly accepted misunderstanding that dyslexia is not specific. Teaching to this misconception is like teaching that the earth is the center of the universe. Much like the responsible sailors, who before the discovery that the world was round would not venture into uncharted territory for fear of risking their vessels, many good teachers are missing out on the scientific discovery that can open new worlds. Dyslexia is actually specific and identifiable. Further, using a more general term like “specific learning disability” hinders teachers and parents from finding the scientific literature on dyslexia, as these more general terms are rarely used in published research articles. Identification of children with dyslexia can guide instruction to be most effective for them. A correct and scientific definition of dyslexia is critical if teachers and parents are to make decisions about reading instruction and intervention for students with dyslexia. Dyslexia is neurobiological, highly heritable (genetic), present at birth, identifiable as early as age 5, and very well researched through neuroscience.4 Copernicus and his telescope opened up a new world. Likewise, neuroscience and brain imaging can inform teachers and parents in the best course of reading instruction for struggling readers, opening their world to all the other information in the curriculum needed in the 21st century. Fortunately, reading is the subject of much neuroscience research. Empirical evidence, studies that are peer-reviewed and that directly test specific instruction methods are guideposts for educators. Scientifically, the validity of research is an important question to assess before investing time and money into programs that are not proven effective for the specific target group.5 If you were in need of treatment for your child’s infection, would you want to try the latest untested herbal remedy that the internet and celebrity gurus are talking about, or the experimental expensive new drug that has been tested in a small group of adult males on one college campus in one specific city? Or would you want the FDA-approved antibiotic that is known to safely and effectively treat that specific infection in children with a 30 year successful track record? Neuroscience and educational researchers have provided clear indications of what the content for dyslexic students looks like, as well as the method of instruction that suits the dyslexic learner. Finding the right content and the methods that will work for all students requires that teachers and parents understand not only what to teach but the sequence and method needed specifically to build the pathways and brain activity of each step in the reading process. Building these pathways adapts the human brain to the printed word in such a way that a person can read text automatically, fluently and with comprehension. Though all learners need to build these pathways, research shows that dyslexic learners only develop these pathways using structured literacy, a prescribed sequence of the content, and the methods of explicit multi-sensory instruction provided with frequency and with ample opportunities to practice each step to mastery before advancing to the next process. Decoding Dyslexia (DDMA) is working to have the scientifically based definition of dyslexia accepted in Massachusetts. Learn more about the goals of dyslexia legislation. DDMA references the experts from the IDA (International Dyslexia Association) and NICHD (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development) who have issued the scientific definition below: Definition of Dyslexia

http://nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/reading/conditioninfo/pages/disorders.aspx International Dyslexia Association (2002) http://eida.org/definition-of-dyslexia/ 1A simple google search with bring up neuroscience and reading research from Shaywitz, Gabrieli, Gaab,, Galaburda, Norton, Pugh, Wolf, Peterson, Pennington, Hoef, Cutting, Eden, Lyytinen, Perfetti, Deheane, and Sherman. I am certainly missing many names.

²Ken Pugh of Haskins Labs describes this process of various brain cells in specific areas of the brain; when we are born, the cells are ready to see and hear and recall without any instruction. He explains that they adapt through learning to build the pathways that allow our brains to read. 3http://www.doe.mass.edu/sped/cspd/sld_notes.pdf slide 6 Slide 6 shows an inaccurate and vague definition of dyslexia, while also having a scientifically referenced definition of aphasia (another SLD). 4http://cercor.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2015/01/09/cercor.bhu305.abstract Norton, E. S., & Wolf, M. (2012). Rapid automatized naming (RAN) and reading fluency: Implications for understanding and treatment of reading disabilities. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 427-452. http://ase.tufts.edu/crlr/documents/2012arop-rapidautomatizednaming.pdf ; Norton, E. S., Beach, S. D., & Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2015). Neurobiology of dyslexia. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 30, 73-78. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266398209_Neurobiology_of_dyslexiaread. 5Long term studies of statistically diverse populations across a wide array of districts or types of schools give us a more valid indication than study in one school or district. Studies that are peer reviewed and hold up to scientific standards and scrutiny before being published are the most accurate and desirable to guide teachers and parents on the types of programs and interventions that dyslexic learners need to succeed. Not all research fits these standards. Comments are closed.

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed