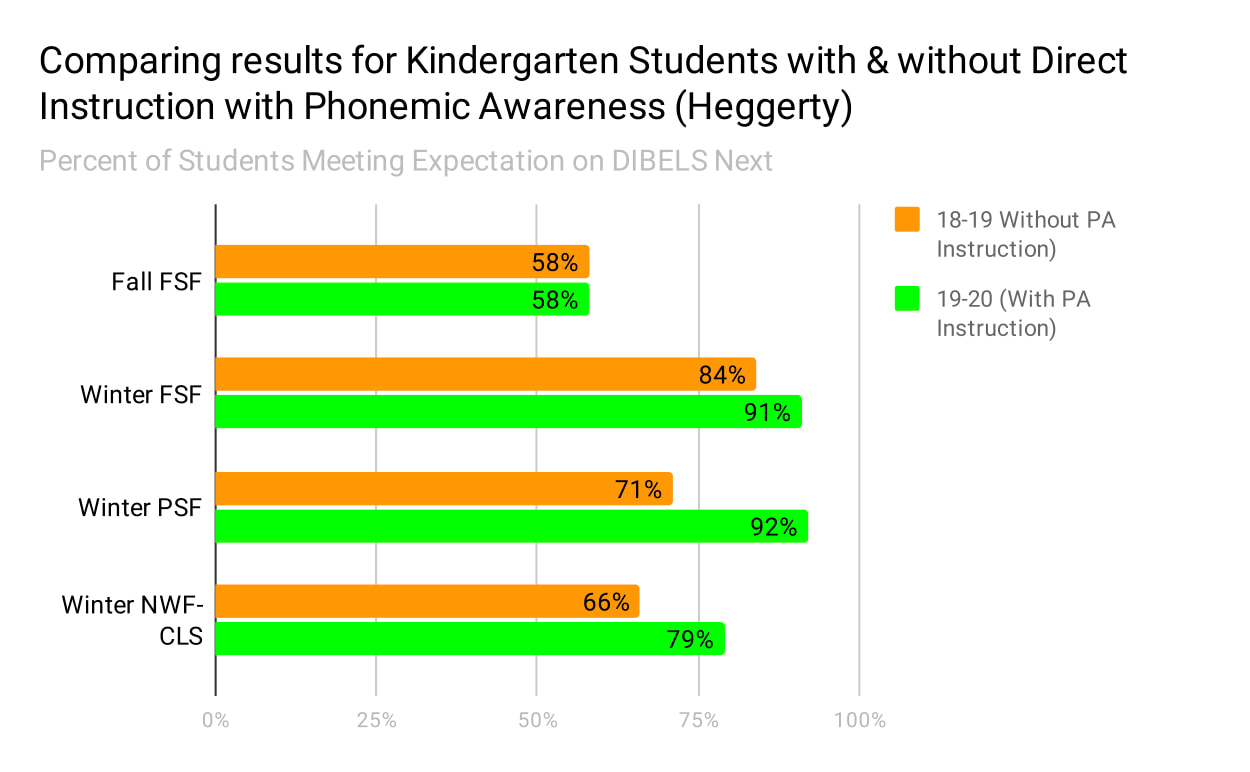

A Conversation with DDMABrent Conway, Assistant Superintendent, Pentucket Regional School District (MA) Mr. Conway is an experienced School Administrator from Massachusetts. While Brent’s background and scope of work for schools is expansive, his passion is with improving literacy outcomes for ALL students. His work as an Elementary Principal led him down a path learning about evidence based practices and whole school change. Many schools use “tiers” but by also applying skills based assessments and taking a scientific approach to a whole school literacy plan he is creating positive changes. For Dyslexia Awareness Month he discussed his work with Decoding Dyslexia Massachusetts (DDMA) Executive Director, Nancy Duggan, answering some questions on how his distinct is approaching reading instruction, assessment and intervention. DDMA: In October, we celebrated all of the professionals and parents who are sharing their stories, resources, and research about Dyslexia to acknowledge Dyslexia Awareness month. Our group spends a great deal of time advocating for instruction for students with Dyslexia. We know it is best handled by highly qualified specialists who can provide the structured literacy reading instruction dyslexic students need to become proficient readers. But, let’s talk today about the importance of general education, with an educator who is applying the science of reading in his district for all students . Can you tell us how science helps determine a high quality curriculum and why it matters for all students? Assistant Superintendent Conway: High quality curriculum and instruction delivered to all students can prevent, or lessen, the need for later intensive services, while also strengthening the foundational literacy skills for students who do not have a disability but simply do better with a structured approach. This hurts no one but actually helps almost all. But not all curriculum focuses on the skills our kids need. A few years ago, we started our work by using assessments that would inform us based on predictive reading skills, those early language skills that research shows predict later reading success. Assessments indicated which skills our students were struggling with and which ones they seemed to be demonstrating quite proficiently. DDMA: The key indicators predicting risk for dyslexia are phonemic awareness, and naming speed, or for emerging readers, letter sound knowledge. Are these areas you assessed and how did this approach impact curriculum? Assistant Superintendent Conway: It was apparent early on that we had no school or district wide general education classroom curriculum or instructional approach to teach Phonemic Awareness to our early and emergent readers. Our data clearly indicated that we had too many students in Grade 1 struggling with blending and too many students in grade 2 and above who were not reading with automaticity and fluency, detracting from their ability to create meaning from text. We took a first step in the Fall of 2019. We implemented and trained teachers in PreK to grade 2 on the Heggerty Phonemic Awareness curriculum. As with any good tiered approach to actually teach a student “We assess back to the point of breakdown - then intervene.” We did the same with our curriculum. We were already using Fundations in Grades K-2 which taught the letters and decoding, but as we looked at the progression of foundational skills, direct, systematic and explicit instruction on phonemic awareness was missing. We assessed it to the point of breakdown, then intervened by adding Heggerty. The Heggerty program provided a simple and easy way to do this. Our teachers immediately started with the 10 minute per day routines, advancing through the sequence. For those students who demonstrated more struggle and were at-risk, they received more than 10 minutes in a small group, sometimes from the classroom teacher and sometimes from an interventionist. DDMA: Can you share the results of this approach? Assistant Superintendent Conway: Yes, the results speak for themselves. The chart below compares how our Kindergarten students did on multiple phonological skills assessments on the DIBELS Next assessments from the prior year to the year we used Heggerty. Even though it is a totally different group of kids, the difference is striking. Their improved ability to segment sounds and its impact on their decoding as well, is solid evidence. We made these decisions based on the reading research and our data matches the expectations. Our teachers are seeing the difference as well. Our early prevention approach with general education dramatically reduced our percentage of Kindergarten students who would be considered at-risk and it likely enhanced all other students' ability to apply the skill more independently.  DDMA: How was scheduling impacted by additional skills instruction for Phonemic Awareness and … of course how will the Covid-19 protocols impact your new approach?

Assistant Superintendent Conway: Our work was obviously interrupted by the closure of schools in the spring and the abrupt shift to remote learning. I know our teachers continued to focus on developing these skills remotely but we did not complete spring assessments. That aside - we know it works and the teachers felt great about where their students were headed. As Neuroscientist, Professor and Literacy expert Dr. Nadine Gaab recently tweeted - in her series of Dyslexia Myths: Dr. Nadine Gaab @GaabLab Most importantly, all struggling readers benefit from early identification & evidence-based interventions regardless of where they live & what caused their difficulties. Learning to read is a basic right, let's all make sure we maximize the joy of learning to read for everyone! 9:04 AM · Oct 1, 2020·Twitter Web App Even in general education the premise holds true. We don’t consider Heggerty, Fundations or any of our General Education curriculum to be “intervention”. If we provide all of our students with the curriculum and instruction that helps at-risk readers, they will all benefit. I am not implying that general education alone will meet all the needs of students with disabilities, like dyslexia. However, if we target these early skills, the skills research shows impact future success, we are addressing needs in a more timely and efficient way. We do know that strong general education can decrease the number of students who need intensive interventions in later grades. DDMA: You mentioned some students even with this early skill development were getting more time with phonemic awareness. So was this skill and instruction providing additional tiered support for all students including those with IEPs? Assistant Superintendent Conway: Using skills based data was also an important tool in making sure that students get what they need, when they need it. If we provide high quality general education instruction and combine that with a tiered approach that focuses on early intervention that is targeted towards precise skills identified by assessment tools like DIBELS, we can dramatically reduce the percentage of at-risk readers and put them on a path for reading proficiency. The science of reading has helped us to know what screening assessment measures are predictors of reading success and which measures can also predict those who are at-risk. Using these assessments in a tiered approach, drilling down further for those who are at-risk to know specifically which skill needs focus, has allowed our general education teachers to work in concert with reading interventionists and special education teachers. DDMA: Parents often hear about reading levels - are the students on or off the level? Can you help parents understand how skill based measures and instruction differ from looking at levels? Assistant Superintendent Conway: Beyond the specific student level focus, using skill based assessments that predict reading proficiency, allows us as a district to see what is working on a larger scale and which general education curriculum and instructional routines are effective. We made a purposeful shift away from reading “levels” as they did not provide us the “why” when a student was behind. Additionally, many times those levels did not correlate with a student’s reading skills that were actually behind, causing a delay in supporting those early skills. Our Assessment Plan combines tools from all three tiers, and provides staff with the big picture of how screening assessments for all students are connected to the more focused and diagnostic assessments for those who are in need. DDMA: It looks like these changes are a step in a very positive direction for your district. I hope your data collection can continue and results in skills improvement for all your students. Assistant Superintendent Conway: We are still in our early stages of our journey to advance our practices but the enthusiasm is present among teachers and administrators even with the unique start to this school year. We are a recent recipient of the Early Literacy Grant from MA DESE: From Research to Practice: Evidence-Based Early Literacy and we are looking forward to our next steps. The recent release of the MA Early Literacy Guidelines which focuses on evidence based curriculum, assessment and instruction for foundational skills is also promising. Myself and other staff in Pentucket were part of the development and we look forward to using it as a roadmap for everyone to see how supporting students who are at-risk is a “group project” and not just the responsibility of a specialist. If we approach this together and coordinate our general education, interventions and special education, the results can be powerful. DDMA: Thank you, Assistant Superintendent for taking the time to share this with us. Explore the new Mass Literacy links from DESE (MA Department of Elementary and Secondary Education.) Mass Literacy is a statewide effort to empower educators with the evidence-based practices for literacy that all students need. Evidence-based instruction, provided within schools and classrooms that are culturally responsive and sustaining, will put our youngest students on a path toward literacy for life. Click the links below to learn more about evidence-based practices and resources that are ready for use in preK-3 classrooms. www.doe.mass.edu/massliteracy/?fbclid=IwAR1wlRqvoP722FM4T9HoVCOUuqqxqFuvF8ONqWPEq3yfDLUOl64qUOYEF5w For more information about Phonological Awareness from DESE https://www.doe.mass.edu/massliteracy/skilled-reading/fluent-word-reading/phonological-awareness.html In collaboration with 10 partners, Decoding Dyslexia announces the release of eight principles that lay the groundwork for future best practice documents that focus specifically on SLD (dyslexia, dysgraphia and dyscalculia). The Principles are formally called: Eligibility for Special Education Under a Specific Learning Disability Classification.

The principles cover topics such as instruction and intervention, collaboration among team members, parent and family engagement, the use of screening, response to intervention, data based decision making and other important factors involved in pre-referral prevention and referral/evaluation and eligibility decisions for special education services for SLDs like dyslexia. Click here to read “Eligibility for Special Education Under a Specific Learning Disability Classification.” It is important to note that this is a consensus document. The Principles are not 100% aligned to DDMA's views on usage of terms, the specific value of cognitive evaluations, and robust parent engagement. DD partners will carefully attend to the work being done and in guidance and advocacy to continue to inform and advocate. However, the benefits of participating in the working group afford dyslexia advocates the opportunity to develop best practice documents as well as work alongside national groups who, until recently, did not "say dyslexia". Working group members hope to continue to build relationships and understanding around the needs of the dyslexia community. The next steps include development and release of several Best Practice documents. In the coming months, these organizations will recommend specific best practices for eligibility processes, cognitive evaluations, response to intervention/MTSS (done well and including dyslexia), parent engagement & a dyslexia guidance. Future additions will be found here: www.ncld.org/SLDeligibility. General advocacy information for learning disability can be found here: https://www.ncld.org/action-center Thanks to Decoding Dyslexia Maryland who originally published this article in their email Newsletter.. Dyslexia is real and relevant. Thanks to Steven P. Dykstra, PhD for providing the following guidance for parents, educators and advocates who are looking for the truth. IN DEFENSE OF THE TRUTH: A REPLY TO 57 READING VOICES ON THE ISSUE OF DYSLEXIA

Dear Decoding Dyslexia Leaders, You may or may not be aware of a letter from 57 backers of balanced literacy sent to officials of the Public Broadcasting System, taking issue with the way PBS covered the topic if dyslexia. The letter is now in wide distribution and is being promoted by Reading Recovery as well as the ILA and its state organizations. If it hasn't come to your state or been sent to your legislators, it will be. The letter is a rehash of lies, but this time we're fighting back and exposing their dishonesty. Attached, you will find my point by point reply, including the letter to PBS and other documents. Please share this widely so you and your members are equipped to expose this dishonest letter for what it is, whenever they encounter it. Steven P. Dykstra, PD Psychologist In Defense of Truth: A reply to 57 Reading Voices on the Issue of Dyslexia

Steven P. Dykstra, PhD Recently, a collection of professors and others wrote a letter to officials at the Public Broadcasting System, taking issue with reports on dyslexia that aired on PBS. The signers of this letter are a list of some of the best-known and most influential reading voices of the past several decades. They are past presidents and officials of the International Literacy Association, members of The Reading Hall of Fame, and authors of books and curricula found in most of the schools and nearly all of the universities in North America. The link to the letter below is hosted by the Reading Recovery Council of North America, purveyor of the widely-marketed Reading Recovery intervention program, completing the triangle with the ILA and university professors that has defined reading instruction and policy in this country for the past 40 years. The common purpose of these partners is to undermine the work of parents and grass roots organizations working to promote the science of reading in opposition to the discredited philosophies, ineffective practices, and failed products the 57 signers prefer. The letter found at this link is also included as Appendix A. https://readingrecovery.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Concern-letter-to-PBS.pdf The letter makes two arguments: dyslexia is a vague and useless concept describing a condition which they imply may not be real, and there is no agreed upon treatment for dyslexia. They cite three sources in their argument: The American Psychiatric Association, Julian Elliott and Elena Grigorenko’s book, The Dyslexia Debate (2014), and the International Literacy Association. It is important to note that many the 57 signers of the letter are or have been major leaders of the ILA, so they are essentially citing themselves. While there are many scientific sources which solidly dispute the claims in the letter, this reply is focused on the two independent sources the letter cites, which I will address one at a time. Dyslexia, the DSM 5, and the American Psychiatric Association The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5thEdition (DSM 5) is a publication of the American Psychiatric Association. The first substantive argument made in the letter is that the APA expressed ambivalence about the validity of dyslexia. “That ambivalence is reflected in the American Psychiatric Association's decision to drop dyslexia as a diagnostic category in the current edition of its Diagnostic Statistical Manual, that field's most respected and widely used reference source.” (page 1 of the letter). Had the APA expressed ambivalence about dyslexia or removed it from the DSM, this would be an important argument. However, it is untrue, and no matter how many times the signers or their followers repeat it, it will remain untrue. The APA did not drop dyslexia from the DSM 5, and they freely use the term without ambivalence. The source of their false claim is a 2013 document from the APA entitled, Specific Learning Disorder (Appendix B) that includes the following sentence: The DSM-5 Neurodevelopmental Work Group concluded that the many definitions of dyslexia and dyscalculia meant those terms would not be useful as disorder names or in the diagnostic criteria. Since that sentence was published 6 years ago, many who dispute dyslexia and reading science have latched on to it to claim the DSM does not include dyslexia and the APA finds the diagnosis problematic. In fact, the sentence only refers to the decision to keep the previous taxonomic structure of the DSM, using the term “Specific Learning Disorder” as an umbrella category which includes more specific impairments in math, decoding, writing, and a variety of other specific skills. Rather than address each of these specific impairments as a category unto itself, the APA chose to maintain the previous structure that treats different learning issues as subtypes of Specific Learning Disorder. This is abundantly clear if the sentence is seen in fuller context: “Just as in DSM-IV, dyslexia will be included in the descriptive text of specific learning disorder.The DSM-5 Neurodevelopmental Work Group concluded that the many definitions of dyslexia and dyscalculia meant those terms would not be useful as disorder names or in the diagnostic criteria.” As the document clearly states, dyslexia is included, just as it was in the past. The APA did not ”drop dyslexia as a diagnostic category in the current edition of its Diagnostic Statistical Manual” as the letter claims. If any signers of the letter wanted to check, they could have looked at page 67 of the DSM 5, which includes the following guidance: “Dyslexia is an alternative term used to refer to a pattern of learning difficulties characterized by problems with accurate or fluent word recognition, poor decoding, and poor spelling abilities.” Including dyslexia as an alternative term should not be taken as ambivalence for the term. The DSM does not commonly allow alternative terminology. This example, along with similar allowances for dyscalculia and dysgraphia, are among the very few, possibly the only, such allowances. Far from distancing the DSM from dyslexia, it embraces the term by going well outside normal practice, as it did in the previous editions, contrary to the false claim in the letter. This is all public knowledge, widely published and explained. It is found in the very document the signers so often cite, and the DSM 5 itself to which they refer, but apparently never read. If the signers needed more evidence of the APA’s attitude toward dyslexia, they could have reviewed the 2018 APA document on Specific Learning Disorders (Appendix C) that lists the three types of Learning Disorders as “dyslexia,” “dysgraphia,” and dyscalculia. The APA uses these allegedly problematic terms with neither ambivalence nor apology. The document uses the term dyslexia eight times, preferring it to alternative terms which are used less often. Furthermore, the APA, recognized as an expert source by the signers of the letter, refers readers to the International Dyslexia Association, a source the signers disparage, for more information, but makes no mention of the International Literacy Association, a source the signers are trying to promote. The APA not only doesn’t take the position the letter signers claim. In important ways, they take the opposite position. This is most striking when we consider the APA’s guidance on the treatment of dyslexia, found in the treatment section of 2018 paper: “Research has shown that the most effective treatments for reading disorder are structured, targeted strategies that address phonological awareness, decoding skills, comprehension and fluency.” This strikes at the heart of the signers’ second claim: that no way of treating dyslexia has been shown to be most effective. The APA, one of only two independent sources cited in the letter, specifically names an instructional approach which the ILA and signers of the letter so often publicly dispute. The Dyslexia Debate, Elliott and Grigorenko, 2014 This important work argues that the term dyslexia serves little purpose in the educational realm, and may do more harm than good by encouraging excessive effort to distinguish dyslexic children from other struggling readers. The authors do not, as the letter implies, dispute the existence of dyslexia. Instead, they take issue with the possible confusion of dyslexia with other causes of early reading difficulty. While many other scholars and scientists take a different view, there is no doubt The Dyslexia Debate (2014) is an important and serious work of scholarship. It must be noted, however, that Elliott and Grigorenko are approaching the issue from both a scientific and practical perspective. Those are two separate debates, but the practical debate is worth understanding in reply to the letter. The core of Elliott and Grigorenko’s practical argument is that spending precious time and resources separating dyslexic children from other struggling readers is wasteful since they all need the same approach, tailored to the needs of each child, built on systematic instruction in the alphabetic principle. Elliott and Grigorenko are unambiguous as to what that instruction must include. Chapter 4 of the book is a systematic take down of whole language and so-called “balanced” approaches that minimize phonics and related skills. “… the suggestion that a common balanced approach is suitable for all children is overly simplistic and potentially misleading…Irrespective of the child’s skills, however, it is now widely accepted that a systematic phonics approach usually leads to superior skills when compared to a non-phonics or nonsystematic phonics approach.”The Dyslexia Debate, Elliott and Grigorenko, 2014, pp, 129-130) Rather than trust my own understanding of their work, I wrote to Julian Elliot to check my interpretation of their position. I wrote: “Here in the US, and elsewhere I believe, the diagnosis of dyslexia has been seen as the tool for unlocking needed intervention. Sadly, it does not in most cases. These children continue to get mostly the same instruction with a heavy dose of multiple cues and various strategies which minimize and obscure the importance of the alphabetic code. As one reading specialist said to me, she teaches phonics to struggling readers if she sees they really need it, whenever they get stuck on a word and nothing else works. The idea of something more planned and systematic was offensive to her.” For me, the finite resources argument is pierced if we simply build the decoding aspect of instruction around those elements science tells us matter most (phonics, phonology, phoneme awareness, morphology, etc) and stop spending precious resources (including time) on approaches which do far less good.” Elliott replied: “Quite agree, Steve.” While I did not reach out to Elena Grigorenko, it is worth mentioning that she serves on the Scientific Board of Directors of the International Dyslexia Association, an organization maligned by the signers. The letter cites Elliot and Grigorenko without understanding their work. It takes their questions about the term dyslexia out of context and ignores the reasoning behind them. Elliott and Grigorenko support the kind of instruction many of the signers reject, the kind of instruction the signers say is not especially effective in addressing reading difficulties. The only way you can accept Elliot and Grigorenko’s argument about dyslexia is to also accept their clear argument that all struggling readers, and all beginning readers, benefit from the same systematic, code-based instruction the letter says is unproven and the signers of the letter have spent their careers resisting. Summary The 57 signers of the letter made a number of false claims, including that the APA rejects dyslexia, that the DSM-5 dropped dyslexia as a diagnosis, and that there is no agreed upon best approach to remediating dyslexia. By promoting this misinformation, the signers themselves are responsible for creating much of the confusion over the term “dyslexia” that they decry. While Elliott and Grigorenko do question the term dyslexia (but not the existence of the disorder) and make important arguments against its use, they do so because all children who struggle to read need the same thing, an approach the letter disputes and many of the signers have worked against for most or all of their careers. We must consider what it says about the state of reading instruction and scholarship that a letter so thick with lies and so thin with facts could attract so many signatures from so many people of influence. By making claims about the DSM and reading instruction which are so clearly untrue, by building an argument on lies and half-truths, the signers have revealed the source of major problems, and it is not in the use of the term “dyslexia.” Appendix A and B are attached in the complete Document Every Reading Specialist in Massachusetts passes the MTEL Reading Specialist Exam to acquire licensure. Other states also use the MTEL for Reading Specialist. - New revisions to the Subject Matter Knowledge (SMK) content guide for this licensure are proposed for PUBLIC COMMENT by March 29, 2019. Important points include:

You can find more information about the SMK for Reading Specialists and find an additional link to complete a public comment survey at this link. www.doe.mass.edu/news/news.aspx?id=25373

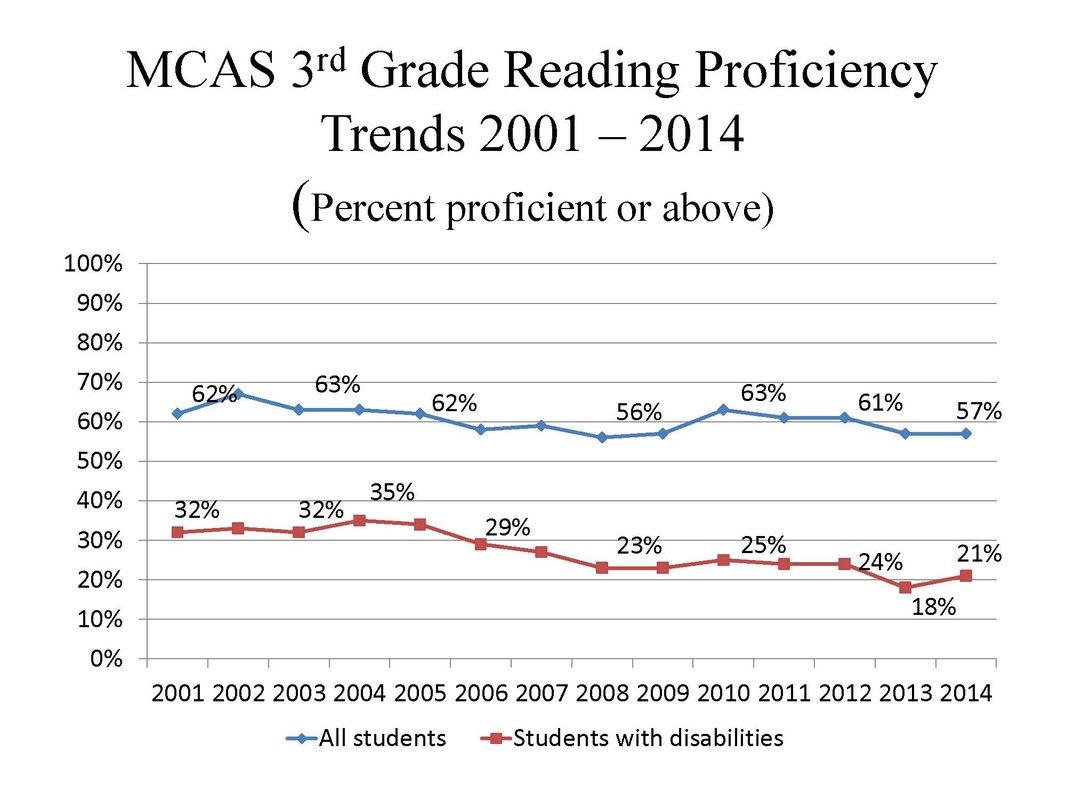

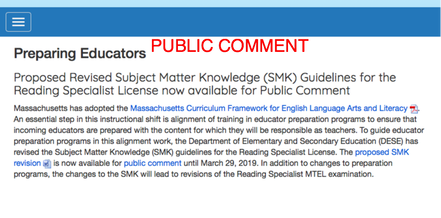

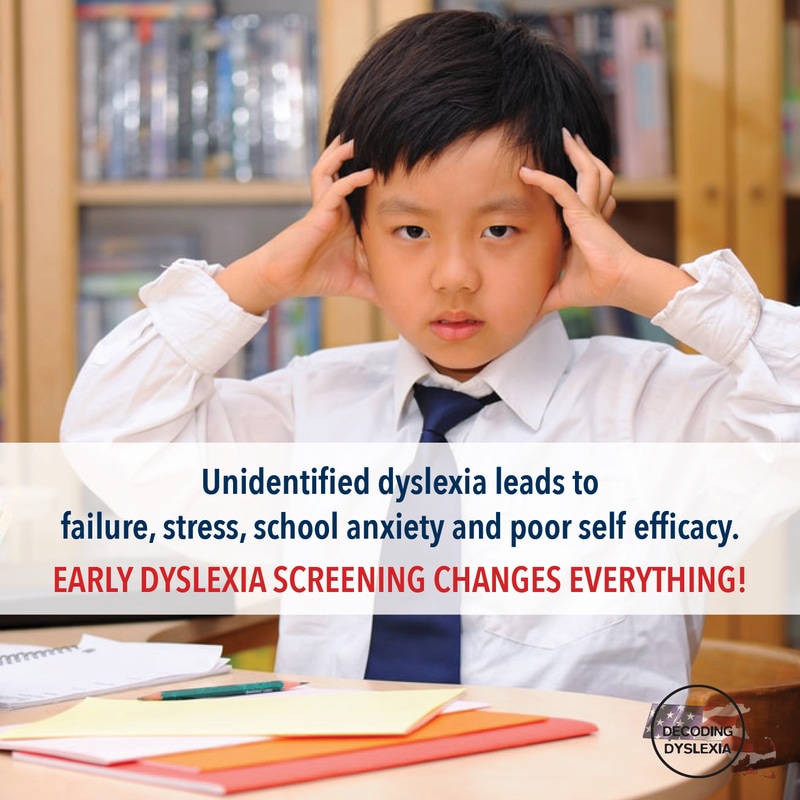

Early Screening for Dyslexia Legislation is a life changing opportunity! Massachusetts legislators will consider Dyslexia Legislation this year and we are asking you to share your experience with your legislators at the State House. At age 5, before formal reading instruction, students with a neurobiological predisposition to a reading disability called dyslexia can be validly and efficiently identified as "at risk for dyslexia". Researchers who have already demonstrated the validity and efficiency of screening in a 5 year National Institute of Health funded study, here in Massachusetts, tell us that the screening can take less that 30 minutes. States like CT, NJ, RI, and NH have already passed dyslexia legislation. Early indicators are highly effective. All students need the foundational skills for reading and the screening will help teachers use interventions that target those pre-reading foundational skills like phonemic awareness, rapid automatized naming, and letter sound knowledge that a student needs. Dyslexic students will demonstrate deficits in these early indicators at age 5 and can begin effective evidenced based instruction while it is most effective, before and while learning to read. This is a ground breaking idea since many people mistakenly believe that dyslexia can not be identified early. Current neuroscience research tells us that not only can we identify at age 5, but that early indentification and intervention is a much more effective way to help these students. Learn more about this research here: www.decodingdyslexiama.org/neuroscience.html The "Paradox of Dyslexia" has been that students are not identified until they fail, but interventions are most effective before they fail. The failure and stress of trying to read without the needed intervention results in stress and anxiety for our youngest students before they have a chance to learn to love school. How real is this stress? Watch the video with Dr. Roberto Olivardia below to learn more about the social emotional factors of dyslexia. Currently in Massachusetts thousands of students are not reading proficiently by 3rd grade state assessments, MCAS or PARC. We know they are struggling but have not identified which students are at risk for dyslexia. Eventually, Massachusetts identifies many students after reading struggle and failure as needing services, but does not have a system to consider dyslexia before the stress of failure and the process of advocating for a full evaluation, wasting years. First students must struggle and fail, sometimes through multiple tiers of instruction. Then students are classified with various less accurate terms. Most parents report that without an outside evaluation some schools refuse to even discuss dyslexia as a possibility. How can they get the help they need sooner and specific to the actual disability dyslexia? Dyslexia is neurobiological, students with dyslexia arrive at kindergarten and first grade and are not ready to learn to read without early direct instruction. These students can be easily identified with a screening process that includes: 1. Phonemic Awareness (PA), 2. Rapid Automatized Naming (RAN) and 3. Letter Sound Knowledge (LSK). Current early intervention rarely includes what is specifically needed for dyslexia. Dyslexia is well researched and known to be neurobiological and evidenced based interventions are also well identified. You can learn more about that here: www.decodingdyslexiama.org/neuroscience.html Statistically, according to the National Institute of Health and neuroscience research, dyslexia is the most common and well researched cause of reading failure. So the majority of students that make up the students with disabilities line are most likely students with dyslexia. Nevertheless in Massachusetts, dyslexia is not considered until after a child is failing. Students with dyslexia are often undiagnosed or misdiagnosed. Schools often refuse to use the word without an outside evaluation. In most cases, schools use the more broad term Specific Learning Disability (SLD). This broad term has frequently been determined to be subjective and used differently in various districts across the state. Other areas are also used subjectively. In Review of Special Education in the Commonwealth, Report Commissioned by Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education it is reported that clear more specific identification would improve services. Instead we learn that in our state: "local school districts are given substantial flexibility in their interpretation of these specific disability categories. In some cases, this appears to result in children with the same underlying issues receiving different disability labels in different school districts. This represents a potential impediment to the effective delivery of services to children and also presents challenges for our analyses. Based on what appears to be the relative diagnostic subjectivity for certain disability categories across the Commonwealth, we combined – as described in Part 1 of this report – children in the Specific Learning Disability, Health and Communication disability categories into one ‘High Incidence’ disability category in some of the analyses reported below." Families, teachers, researchers and students of the Commonwealth would all benefit from more clarity. Dyslexia is defined and well researched by the National Institute of Health. Congress in the recent READ Act, in IDEA and ADA laws mentions dyslexia specifically as a particular disability under the SLD broad category. Providing this definition would be very beneficial. The Office of Civil Rights and the Department of Education issued Dyslexia Guidance in October 2015 informing states that there is no reason to avoid the specific disability name, dyslexia and also that when using SLD category the actual disability may inform decisions on how to provide services. Decoding Dyslexia has adopted the hashtag #SayDyslexia to raise awareness that naming dyslexia can guide better, more effective delivery of services. Please complete this form to let us know who has been contacted so we can have other legislators and staff follow up. For the Massachusetts House use this link: goo.gl/forms/W04xYxCxie1NIeG82 For the Massachusetts Senate use this link: goo.gl/forms/ES3F02dZ7jTITImF3

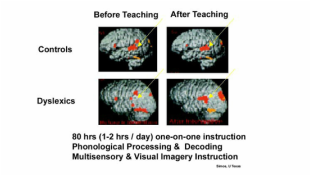

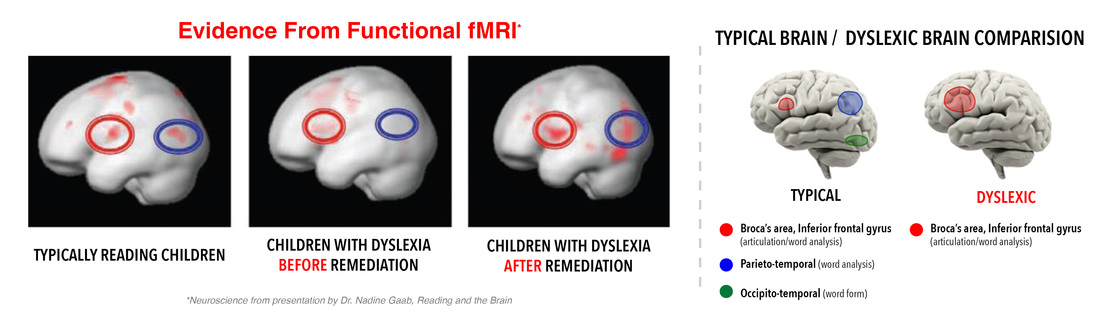

By Nancy Duggan  Legislators in Massachusetts are beginning to #SayDyslexia. DDMA says thank you! Thanks to the many families that continue to speak up and explain the challenges of dyslexia faced by public school students in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and the important and most valued help of dyslexia experts in the fields of neuroscience, literacy and speech and language, we have made another step toward improving education for students with learning disabilities, especially dyslexia. We are not there yet but we are making progress! On Friday, An Act Relative to Providing Screening for Dyslexia was moved forward (But not yet passed into law) in a redrafted version (A NEW BILL NUMBER WILL LIKELY BE ANNOUNCED THIS WEEK) . As we wait to see what the next step will be. I urge everyone to look at this Bill which amends an already established law, very carefully. There is much to be happy about; I want to point out some of the positives: 1. Our legislators have heard our concerns and are taking legislative action. It is very clear that our efforts are not wasted and the #SayDyslexia and #ScreenDyslexiaMA 2. The title of the Bill clearly states the intent of the law: "to Provide Early Screening for Dyslexia." 3. As currently written, the law includes "a voice for families whose children are struggling with dyslexia in the public school system and requires research-based recommendations". We have traveled far to get this to happen and we need to keep it moving in a positive direction. Initially when you read the bill you may, as I did, ask: Where is the definition? Why this Panel? Or have other concerns with the specifics of the legislation. Although it is not the immediate result of screening by next year, that legislation in NH recently passed; It is something that we have not had ...it specifically says "early screening" and if it passes: directs by law the established Early Literacy Panel to take: "steps to implement the research-based recommendations contained in reports written by experts in early language and literacy development with respect to reading disabilities including dyslexia; provided that, in developing its recommendation, the panel shall solicit at least one organization representing families with dyslexia." It could still change as it goes through the legislative process. We have questions - but lets support this while we ask them and hope that our questions inspire clarification and a more effective outcome. 1. What is the definition to be used when discussing "early screening of dyslexia"? Specific Learning Disabilities includes dyslexia, so not all specific learning disabilities are neuro-biologically dyslexia, and the term "reading disabilities" is also broad and not specific. The brain imaging research and neuroscience that enlightens us is fairly recent in scientific terms, and is specific to the scientifically defined dyslexia using IDA/NIH definition. If we are part of the conversation we can explain more about why this matters. We are fortunate that the expert research laboratories in our state studying dyslexia can provide, and have provided, testimony, guidance and a desire to collaborate with educators and share the latest accurate research for dyslexia. 2. What will it mean for dyslexia screening to be considered by the panel? General screening is already part of the process in most schools (but not for dyslexia ). The current Early Literacy Panel, by law advises about screening, and training of teachers and early educators to screen. Let's hope that if we proceed we will see not only screening protocols for dyslexia endorsed by the panel, but guidelines and training of how to screen for early educators and teachers. Research clearly supports early intervention and we will have to stick with this to see it unfold. I think this is a good step. 3. The current Literacy Panel, and the Third Grade Proficiency Law that establishes it includes the following: on the alignment, coordination and implementation of, including, but not limited to, the following areas: (1) strategies for evaluating the effectiveness of curricula on language and literacy development for children in early education and care programs and grades pre-kindergarten to third grade, inclusive, that (i) is anchored in rich content; (ii) uses a wide variety of types of text to support content under study; (iii) emphasizes the role of oral language and discussion in promoting early reading skills; and (iv) contains a balanced instructional design focused on developing both meaning-based skills, such as comprehension, conceptual knowledge, vocabulary and code-based skills, such as letter knowledge, letter sounds and word reading; For students with dyslexia aligning with this specific criteria may or may not align with what is the necessary research evidenced based dyslexia instruction. How can the panel ensure that these criteria are adjusted for the evidenced based criteria for dyslexia? We can bring that question forward with us, guided by dyslexia specialists in instruction. Massachusetts has IDA endorsed programs and some excellent literacy experts who focus on dyslexia. Fortunately they are committed to helping move early screening for dyslexia in Massachusetts. So now what do we do? 1. Call your legislator and thank them for supporting Dyslexia Legislation. 2. Remind them that the scientific definition matters not only for screening but for the current students struggling and ask them to consider that as they go forward with their support for dyslexia legislation they remember that current students would benefit from acknowledging an scientifically accepted definition, like the definition used by the National Institute of Health. This is an important step in better outcomes for students with dyslexia and all students with learning disabilities.  Nancy Duggan, Executive Director, DDMA Some children do not read proficiently by third grade even when parents and teachers seem to be doing all they can. What does neuroscience tell us about this problem? Researchers have been studying the process of how we learn to read for over 30 years using Neuroscience. That is not a long time in the world of science. We have been studying the planets scientifically since Copernicus in the 1500s. With that kind of time invested, no wonder we could send rockets to the moon before our kids were born; but teaching them to read remains a challenge. What we now call dyslexia was first mentioned in the 1870s. But just as Copernicus and his telescope started scientific study in the 1500s, proving that the earth went around the sun, which over time lead us to walk on the moon, using neuroscience and brain imaging technology to study dyslexia has advanced what we know about how brains learn to read. These advancements, if transferred to the classroom, could improve reading for dyslexic students. Neuroscience1 recently has been making great strides in dyslexia research and MRI technology has played a part. In particular, fMRI technology which uses a Magnetic Resonance Imaging process to make observations of how brains are functioning (the f in fMRI). Scientists are able to evaluate the areas of brain activity and the amount of energy that our brain’s specialized areas are using. There is not one area of the brain that is dedicated to reading. Neuroscientists explain that there are many areas of specific brain activity that naturally process vision, language and/or memory. These areas must be taught to work together, these multiple areas communicating through brain pathways are built by learning.2 By using many fMRI images together neuroscientists observe changes and developments that indicate how these regions are working, and working together, in good and poor readers. Our brains are constantly adapting and changing as we learn and the ability to make these observations has provided evidence of the differences that can naturally occur between individuals trying to adapt and learn the process of reading. Neurodiversity or cerebrodiversity are new terms to reflect the differences in healthy functioning brains that process differently from each other. Understanding the differences in brain processing, in what Dr. Nadine Gaab describes as the typical and atypical (ADHD and/or Dyslexia) reading brain, is a valuable consideration when choosing instruction, intervention and assessments for reading instruction of all students. Dr. Gaab and colleagues have found that these differences are present at birth and Dr. Gabrieli and Dr. Norton provide evidence that as early as kindergarten, it is valid, effective, and advisable to screen for these differences and actively ensure that instruction is specific to the needs of these children. They are not alone in their research and there is ample evidence for the neurobiological existence of dyslexia. Unfortunately, like many folks in the time of Copernicus who did not at first believe or understand that the planets went around the sun because they had been taught that the sun circled the earth, many educators have been told that dyslexia is not real or doesn’t matter. Likewise, even when the word dyslexia is used, parents and teachers who are using the word without the current neurobiological meaning and the implications of the latest research may not find the specific instruction that will be effective. For example, the SLD (Specific Learning Disability) Module of instruction for the Massachusetts Department of Education incorrectly describes dyslexia as a common term that is used for “the reading related manifestations of learning disabilities”.3 This highlights the commonly accepted misunderstanding that dyslexia is not specific. Teaching to this misconception is like teaching that the earth is the center of the universe. Much like the responsible sailors, who before the discovery that the world was round would not venture into uncharted territory for fear of risking their vessels, many good teachers are missing out on the scientific discovery that can open new worlds. Dyslexia is actually specific and identifiable. Further, using a more general term like “specific learning disability” hinders teachers and parents from finding the scientific literature on dyslexia, as these more general terms are rarely used in published research articles. Identification of children with dyslexia can guide instruction to be most effective for them. A correct and scientific definition of dyslexia is critical if teachers and parents are to make decisions about reading instruction and intervention for students with dyslexia. Dyslexia is neurobiological, highly heritable (genetic), present at birth, identifiable as early as age 5, and very well researched through neuroscience.4 Copernicus and his telescope opened up a new world. Likewise, neuroscience and brain imaging can inform teachers and parents in the best course of reading instruction for struggling readers, opening their world to all the other information in the curriculum needed in the 21st century. Fortunately, reading is the subject of much neuroscience research. Empirical evidence, studies that are peer-reviewed and that directly test specific instruction methods are guideposts for educators. Scientifically, the validity of research is an important question to assess before investing time and money into programs that are not proven effective for the specific target group.5 If you were in need of treatment for your child’s infection, would you want to try the latest untested herbal remedy that the internet and celebrity gurus are talking about, or the experimental expensive new drug that has been tested in a small group of adult males on one college campus in one specific city? Or would you want the FDA-approved antibiotic that is known to safely and effectively treat that specific infection in children with a 30 year successful track record? Neuroscience and educational researchers have provided clear indications of what the content for dyslexic students looks like, as well as the method of instruction that suits the dyslexic learner. Finding the right content and the methods that will work for all students requires that teachers and parents understand not only what to teach but the sequence and method needed specifically to build the pathways and brain activity of each step in the reading process. Building these pathways adapts the human brain to the printed word in such a way that a person can read text automatically, fluently and with comprehension. Though all learners need to build these pathways, research shows that dyslexic learners only develop these pathways using structured literacy, a prescribed sequence of the content, and the methods of explicit multi-sensory instruction provided with frequency and with ample opportunities to practice each step to mastery before advancing to the next process. Decoding Dyslexia (DDMA) is working to have the scientifically based definition of dyslexia accepted in Massachusetts. Learn more about the goals of dyslexia legislation. DDMA references the experts from the IDA (International Dyslexia Association) and NICHD (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development) who have issued the scientific definition below: Definition of Dyslexia

http://nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/reading/conditioninfo/pages/disorders.aspx International Dyslexia Association (2002) http://eida.org/definition-of-dyslexia/ 1A simple google search with bring up neuroscience and reading research from Shaywitz, Gabrieli, Gaab,, Galaburda, Norton, Pugh, Wolf, Peterson, Pennington, Hoef, Cutting, Eden, Lyytinen, Perfetti, Deheane, and Sherman. I am certainly missing many names.

²Ken Pugh of Haskins Labs describes this process of various brain cells in specific areas of the brain; when we are born, the cells are ready to see and hear and recall without any instruction. He explains that they adapt through learning to build the pathways that allow our brains to read. 3http://www.doe.mass.edu/sped/cspd/sld_notes.pdf slide 6 Slide 6 shows an inaccurate and vague definition of dyslexia, while also having a scientifically referenced definition of aphasia (another SLD). 4http://cercor.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2015/01/09/cercor.bhu305.abstract Norton, E. S., & Wolf, M. (2012). Rapid automatized naming (RAN) and reading fluency: Implications for understanding and treatment of reading disabilities. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 427-452. http://ase.tufts.edu/crlr/documents/2012arop-rapidautomatizednaming.pdf ; Norton, E. S., Beach, S. D., & Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2015). Neurobiology of dyslexia. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 30, 73-78. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266398209_Neurobiology_of_dyslexiaread. 5Long term studies of statistically diverse populations across a wide array of districts or types of schools give us a more valid indication than study in one school or district. Studies that are peer reviewed and hold up to scientific standards and scrutiny before being published are the most accurate and desirable to guide teachers and parents on the types of programs and interventions that dyslexic learners need to succeed. Not all research fits these standards. “There are times as a parent when you realize that your job is not to be the parent you always imagined you’d be, the parent you always wished you had. Your job is to be the parent your child needs, given the particulars of his or her own life and nature.”

--Ayelet Waldman Written by Nancy Duggan As the mother of three adult children, I know that almost any parent can look back and identify the times they wished they had figured things out sooner. If the “particulars” of your child’s needs include dyslexia, as they did for my youngest, recognizing what your child needs and how to be that parent is a unique challenge. You may wish you had more training for the job. Somehow you are trying to manage social, emotional, and academic issues that appear typical to others, yet the typical solutions and guidance seem to add to the problem. You need a compass and a good map. My journey started 20 years ago. I knew my daughter was bright and motivated, but was behind her peers academically and not reaching the milestones her siblings had easily met. When I inquired about the path I should take, every teacher warned me not to compare, to give her time. After all, “she is a delightful child.” So I sat tight—I didn’t want to be that over bearing parent who caused teachers stress. When it finally became apparent to her teachers that needing a little more time was not the issue for my daughter, she had become understandably stressed. One of the oldest in her class, she was clearly intelligent, but I had an 8 year old facing fourth grade with literacy skills below kindergarten level. This was despite 2 years of preschool and 4 years of primary school—and yes, I read to my child, thank you very much! Finally, somebody said “dyslexia.” One word turned the typical childhood path of academia into unchartered territory, and there was much to learn about the new and unfamiliar terrain for this journey. My dad used to say, “when all else fails, follow the directions.” I found myself learning about dyslexia, Orton-Gillingham, resilience, and child development. My research exposed me to some fascinating insights into how children succeed academically and socially and, not wanting to waste any more precious time, I became an informed consumer. Once I had familiarized myself with the terrain of parenting a child with dyslexia and knew the destination for which we were headed, I discovered my child was the compass to direct our path. I was forging the trail, but would go in circles without reading the compass. With this in mind, I share a few travel tips for the journey of raising children with dyslexia:

|

|||||||||

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed